Research has shown that light pollution causes problems for both wildlife and humans. In the Star-Spotting Experiment we also want to learn more about what we can do to reduce light pollution and use light in an optimal way. At Jönköping University in Sweden researchers are working with these questions. Myriam Aries is a Professor in Lighting Science, and we asked her to answer a few of our questions.

Myriam Aries’ research focuses on the interaction between humans and the integration of light in diverse architectural environments. Myriam’s colleague Annika Jägerbrand, a Senior Lecturer in Lighting Science was also involved in answering some of the questions.

What is your research about?

My research is about understanding how light impacts human beings and what we can do with light in the built environment to help people feel good and stay healthy. I want to know how we can use lighting to support people when they want to read and write, or to see the environment around them. Light also influences our biological clock and helps us sleep and wake up.

The amount and the colour of the light as well as the moment that people need light and for how long varies at different times of the day, in different environments, and for different people. We are investigating what the ‘right’ lighting is for humans at various moments during the day and at different stages in their lives. It might be at home, at the office, at school, in hospital, in a home for the elderly, outside, or when travelling around.

Is it fun to be a scientist?

Yes, it is fun to be a scientist because researchers can be curious and set up experiments to test and investigate how things work. All people know what light is, know that they need it to see, and many people also know that when you take a long flight to the east or west side of the world, that you won’t want to sleep at the same time as you should s at your destination. Even though my research area is actually very complicated, most people have personal experiences with lighting, and it seems easy to understand what I’m doing.

The problems with light pollution have been increasingly recognised lately. What do you think is the biggest problem with the way we use artificial light today?

Artificial light is basically always present. In former times, when people did not have electric lighting or it was only very limited, they would be active when there was daylight and then relax or sleep when it was dark. When the sun comes up, our body receives a signal that it is day and it prepares us for the day and being active. Since there is always light around now, our bodies can get a little bit confused and may give us the wrong signals at times. Our sleep quality is not as good as it could be and that is unfortunate since humans need sleep to restore and repair our bodies. A good sleep requires total darkness and with electric lighting being everywhere this is not easy to accomplish.

Is there any research on how we should reduce light pollution in the future?

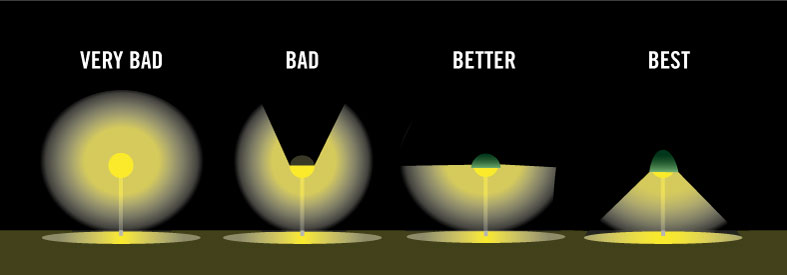

There is an international effort aiming to establish a metric for measuring obtrusive light and light pollution. Currently, we do not have a common methodology to measure light pollution, which makes it difficult to reduce light pollution by legislation and regulations. Research is trying to limit light pollution and the impact of lighting at night in many ways. One way is to see if we can direct the light precisely where we need it. If we need light on the road to make drivers, pedestrians and cyclists feel safe, the design of the luminaire (light unit) is optimised to direct the light exactly where it is needed and not spread it, for example, into the sky. With sensors, researchers and lighting designers are finding ways to turn luminaires on only when there are people present: no people around, no lighting active. There are even experiments using drones, equipped with spotlights, flying close to cars to provide the illumination only for that vehicle.

Another focus of researchers and lighting designers is to optimise the quality/quantity of the lighting itself. We know, for example, that different light levels and colours (part of the light spectrum) have different effects on people and we are looking at ways to prevent sleep disruption by preventing light from entering people’s bedrooms or by removing the ‘blue’ of the lighting, for example. It has recently been pointed out by researchers studying insects that the strongest contributor to insect decline is artificial light at night, and that exterior lighting needs to be reduced. It is most likely not enough to only optimise the spread, but the lighting intensities that we use must also be lowered to avoid impact on the insects.

What are the most important actions we could take to reduce the problems with light pollution?

The general recommendations for reducing light pollution are:

- Prevent / limit new areas being illuminated

- Limit the extent of illuminated areas

- Limit the time of illumination

- Limit the illuminance level

- Adjust color of light source (to reduce the ecological impact)

- Reduce, improve and adapt the light in or near protected areas

The implementation of ALARA, As Low As Reasonably Achievable, should be used when planning lighting.

We should continuously critically assess situations where there is light at night to see if the light is actually required there (or at all times). We can all look at the lighting in our homes and companies to check that most of the light is not being shone into the sky at night. If there is any doubt, lighting professionals can help to assess and improve the situation. Improvements can be made by optimising the amount of light, the luminaire/lamp efficiency, and the distribution to avoid light radiating into the sky or to parts of the surroundings where it can bother others (traffic participants, animals) via the design of the luminaire or the use of sensor technology.

Other countries have implemented legislation to avoid increasing light pollution, such as Italy . France has adopted strict legislation to avoid light pollution, probably the most strict legislation in the world today. Sweden does not have any legislation against excessive use of exterior lighting.

Do you or your colleagues collaborate with any municipalities or cities in Sweden to develop urban lighting?

We are not directly developing urban lighting ourselves at the university, but we are investigating the impact of lighting on humans’ lives, and that knowledge is being used by industry and municipalities to develop urban lighting. We are collaborating on this with municipalities and energy suppliers/distributors to better understand their needs and the opportunities. The university also offers a bachelor course in Lighting Design, and the design of urban lighting is a large part of the programme. The students undertake city walks together with people from the municipality, and our students complete lighting exercises at night. They design the lighting and test the effects and impact on the surroundings, the environment, animals, and people.

We sometimes collaborate with municipalities on research projects to involve them in the research and ensure that the knowledge from the research is shared prior to the implementation phase.

For more information, please contact

Prof. Dr. Myriam Aries ([email protected])

Dr. Annika Jägerbrand ([email protected])